Can ‘Cosy’ Be Learnt?

As anyone who knows me will tell you, I am essentially a reptile. I’m not scaly or slimy, but I am, in truth, cold-blooded. A sun-worshipper who would happily live all year in Mediterranean summer and forgo winter entirely — save for one weekend by a fireplace and perhaps the weeks and hamlets of winter perfect for the act of skiing. I resent the change of season and am utterly baffled by people who romanticise the colder months.

Recently, while travelling, I admitted out loud, to general horror, that while everyone else seems to love the leaves changing colour, it actually makes me feel melancholy. The seasons of Spring and Summer that I patiently wait for (if I’m being honest, live for) are closing out, and I’m forced to swap my linen and bikinis for balaclavas and gloves. In an attempt to understand why this feels so dramatic to me, I started reading about winter like it was a foreign language. Katherine May writes in Wintering that “to get through winter is not a punishment, but a practice.”

Now, I’m not a monster; I can understand the appeal of the romanticised imagery of winter. A small, distant appeal, but still. I understand why winter sounds beautifully enticing to people. The problem is that the deliciousness with which winter people describe the season doesn’t land naturally for me. I can see why people like it conceptually but it’s a feeling I can’t quite access. Like a sneeze that won’t come, or trying to pop your ears on an airplane. I know what is supposed to happen…but I can’t quite get there. My current working theory is that I’m missing a key personality ingredient: the cozy gene.

This theory was only amplified by my recent move — or partial migration — back to Dublin from Barcelona. I am, by temperament and biology, a tomato-Europe woman, not a potato-Europe one (passport aside). Those who thrive in the Celtic latitudes, in my opinion, are categorically “cozy people”. I, on the other hand, have the winter constitution of an overly-tended-to houseplant. I am not one of those who light candles just after noon when the sun starts its premature descent, own several varieties of blanket, and understand what a “stew night” is. Those who own thick house socks and look great in woollen knits. Those who believe there’s no such thing as “bad weather.” If I’m being real, I’m the sort of person who thinks winter styling is just ‘add a coat’ and that grey skies are karmic punishment.

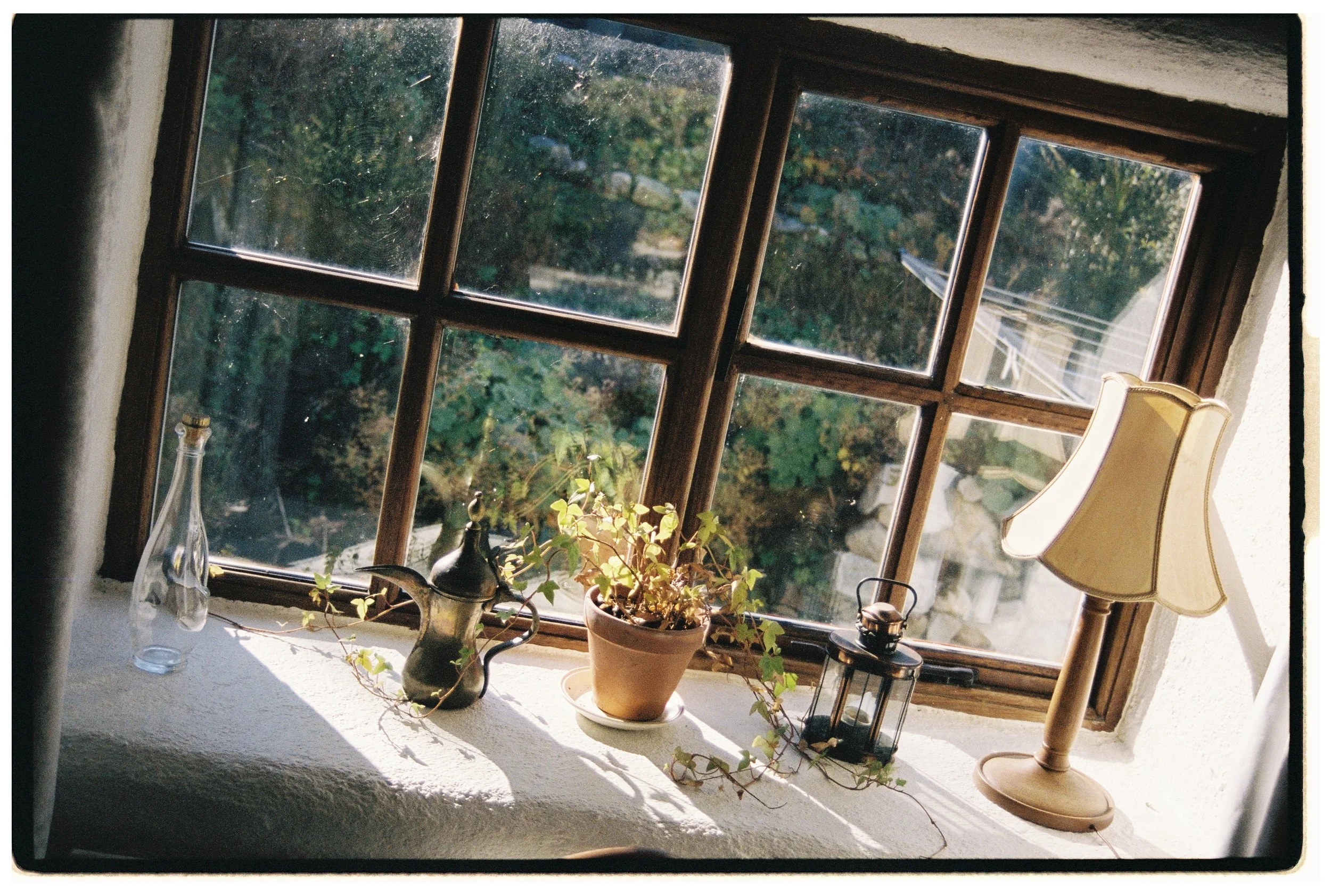

I would always rather be lying on a rock in the Mediterranean — salted, toasted, and flirting with warm water seas — than hiking a mountain surrounded by heather and thrush. I’d rather sit barefoot in a beach club than in a firelit snug with a beer. I look at photographs of the Cotswolds in the cold and think “oh how beautiful”...but ask me to go there from November onwards, and I tense.

So I started wondering: is coziness innate or can it be learned? Is it nature vs nurture? Are some people just doomed to forever pretend they enjoy ‘crisp winter walks’ or can a person like me - reptilian, sun-fuelled and spiritually Sicilian- make peace with the cold?

There’s another layer to this curiosity. Some of the people I love most are natural winter people. My best friend, for example, who has lived in Ireland for almost a decade, moves through winter with a kind of innate grace I can’t replicate. She reaches for knits effortlessly, swims in lakes out in the wild Atlantic west, and finds relief when the air turns cold and the summer finally stops trying so hard. Watching her has made me quietly envious — the ease with which way she inhabits a season I’ve spent my whole life resisting.

It’s made me realise that part of my yearning to “get better at winter” is bound up in affection — the desire to understand and perhaps even enjoy something because people I love, love it. Because they don’t seem tortured by it. What am I missing? As I get older, I’m starting to resent myself for living only for a small window of the year. I want more of the calendar to feel like mine.

And here’s where the sartorial creeps in — quietly, inevitably.

I’m a bare-feet-before-wellies, lace-before-layers sort of woman. The kind who dresses for June even in November. My wardrobe is built for Aperitivi, not Arctic blasts. Perhaps the cold only feels cruel when you try to outwit it — when you dress as though winter is a rumour rather than a reality. Maybe coziness begins in the body, not the candle aisle: in choosing fabrics that hold heat rather than let it leak out of you. If I dressed for winter with the same intention I bring to summer - the same affection, the same romance - might I feel different inside it? Maybe layers aren’t a compromise but a form of care. Maybe the right coat isn’t defeat, but devotion.

So this season, I’ve given myself a challenge: to learn to love winter. Or at the very least, to carve out in my heliophile heart a place where the colder months are more than just survivable.

Which raises new questions. Could the solution be as simple as a better winter coat? A dry robe after Ireland’s unofficial sport: wild swimming? Can sartorial shifts create emotional shifts? Does better lighting, antique floor rugs, a winter fireplace make a real honest-to-god difference? As a self-proclaimed hedonistic aesthete, could hunting down some beauty move the dial?

To investigate, I turned to someone I have privately coined the ‘Queen of Cozy’ — Vogue contributor and interiors whisperer Chloe Frost-Smith — to see whether my theory held any weight. Because, let’s be honest: I’m jealous. Looking at Chloe’s work and travels, she seamlessly navigates her way around the Scottish Highlands and English countryside, infuriatingly, making layering look like an effortless personality trait.

“I wasn’t always a winter person,” Chloe tells me. “But since moving to Scotland, I stopped resisting the cold and started leaning into it… Now I look forward to this time for its slowness, softness, and invitation to turn inward.”

However, turning inward doesn’t mean hibernating inside, as I have so often assumed.

“One of the most non-obvious ingredients of cosiness is actually getting outdoors,” she continues. “In Norway they call it friluftsliv — open-air living. The indoors only truly feel cozy when you’ve first been out in the elements. When you come home wind-chilled and flushed and let warmth sink back into you… that’s the essence of it.”

This idea — that coziness is earned, not merely staged — is food for thought for me. Perhaps my aversion wasn’t to winter itself, but to the performative version: the forced hygge without the fresh-air prelude. Or perhaps coziness is a reward rather than a result. Or maybe, in the words of the great Billy Connolly, there is no such thing as bad weather, only “the wrong clothes.”

Chloe pointed to the vocabulary of northern cultures - hygge (Danish), koselig (Norwegian), mys (Swedish), coorie (Scottish) - not as clichés but as clues. Each expresses a balance between nature’s wildness and the sanctuary built indoors. Coziness, she argues, is less about wool blankets and more about rhythm: the ebb and flow between outdoors and in, dark and light, slowness and spark.

By this point in my questioning, I feel myself softening, just a little, to the idea that winter might be more than something to survive, perhaps because the people I admire have found their peace with this season.

So maybe cozy people aren’t born so much as built. Maybe the “cozy gene” is less genetic destiny and more an accumulation of choices: layers that fit, lighting that flatters, rituals that restore and outdoor moments that give the indoors meaning.

Somewhere underneath all of this - beneath the coats, the candles, the cold - is the quieter truth that keeps tugging at me: I don’t want to feel left out of half my own life. I want to understand the season the people I love step into so naturally, to feel connected to the rituals and rhythms that give them joy when the world darkens. I want to stop shrinking myself to one sliver of the year and start belonging to more of it. That longing, that envy, that tenderness. Perhaps that’s the real reason I’m trying.

Ultimately, I’m curious as to how helpful it is to keep asking whether I was born cozy, and whether the gift is genetic, inherited, or temperament. Maybe the better question now is simply whether I want to be. And the answer is yes — or at least, enough to try. To dress intentionally, to brave the outdoors, to let warmth be something I build rather than wait for. I won’t pretend I’m a convert yet, but I am going to give it a crack this season. I’m trying to make winter, for the first time, feel less like exile and more like an invitation.

And perhaps that’s all the coziness I need for now.