A City That Disappears in Order to Be Loved

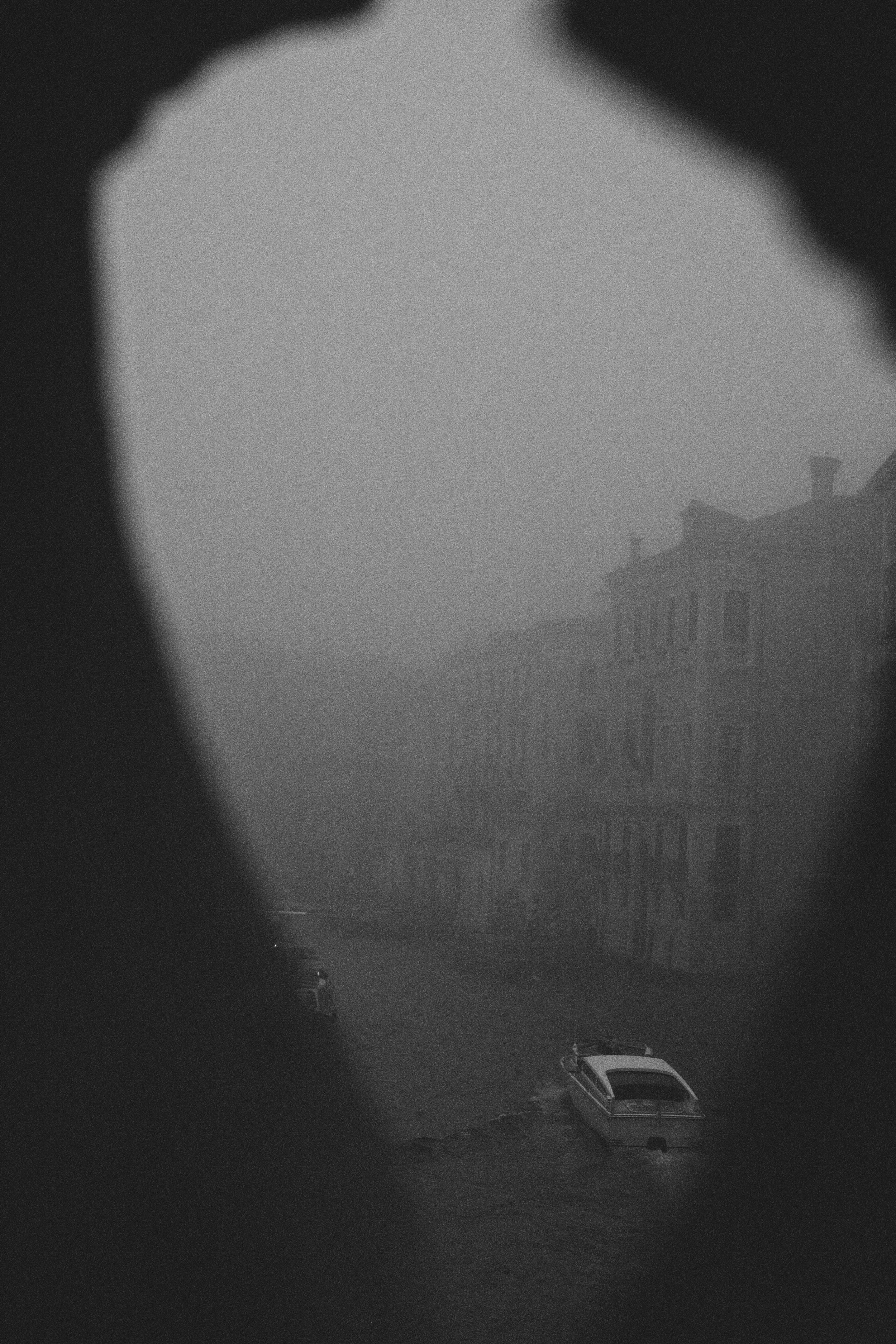

Caìgo (Venetian dialect) : a word for the thick lagoon fog that swallows distances. Often linked to older forms meaning something like a mist/veil that “takes” the city: it doesn’t just arrive, it occupies. In English you might call it fog, but that misses the point. This is fog as mood, fog as method.

I didn’t leave home this morning with a plan. In Venice, especially in winter, plans feel like an imported habit; useful, perhaps, but slightly ridiculous. You step outside and the city immediately negotiates with you. It doesn’t promise you anything. It simply offers a direction and asks what kind of person you intend to be today.

And today the air had decided for everyone. The first thing I noticed wasn’t what I couldn’t see.

It was what I could.

The nearby things, suddenly promoted, suddenly important. A threshold. A wet stone. The small geometry of paving darkened as if the night had decided to linger on the ground even after leaving the sky. The lamplight under an arcade, hanging there like a patient thought.

There are cities that belong to daylight. They want edges, definition, clarity. Venice doesn’t. Venice belongs to whatever softens. It was built on water, held together by stubbornness and repair and it seems to understand, better than most places, that the world is never as solid as it pretends. In summer, the city plays along with the fiction. It gives you views, grand perspectives, all that theatrical generosity. In winter it returns to its true nature: quiet, private, almost inward. The season teaches Venice how to be a person again, not a spectacle.

I walked without checking the time. That is already a small kind of luxury here. You learn to live by other clocks, by the rhythm of shutters opening, by the sound of a delivery boat turning in the canal, by the moment a barista wipes the counter and looks up as if to say: allora?

You learn, too, that Venice is not one city but a hundred: each field, each calle, each corner is its own weather system and temperament. And on mornings like this, those temperaments blur into one long sentence. Under the arcades the air felt padded, as if the city had wrapped itself in wool. Sounds don’t travel. They arrive softened, domestic, like a voice coming from another room. Even water (the most talkative element here) seems to speak lower. I passed a closed door and for a moment imagined the life behind it: the kettle, the radio, the faint heat of a kitchen, someone moving in slippers. Winter in Venice is full of these invisible interiors.

And then, without warning, the world opens and empties at the same time. At the end of a passage the city simply stopped. No horizon, no reassuring line of elsewhere; just brightness, an expanse that wasn’t exactly white and wasn’t exactly grey, like paper that has absorbed too much light. The lagoon was there, of course, but not as “lagoon,” not as geography. It was presence without borders. A boat was moored nearby, half-claimed by the air, as if it had been drawn and then gently erased. It looked lonely in the way only Venetian boats can look lonely: not tragic, not abandoned, just quietly obedient to whatever the water decides.

This is what that fog does. It doesn’t merely hide; it edits. It removes the unnecessary so the essential can speak. It forces the city to stop performing itself.

I stopped in a small courtyard where a gate stood half-open, as if undecided. Beyond it, a patch of green: not much, but enough to feel like a secret. That is another lesson of wintering here. The city’s true riches are not always in the obvious places. They are in what stays hidden. In what only reveals itself to those who have time to be unproductive. A city like this rewards the person who is willing to waste an hour on a corner.

I took out the camera and lifted it, but even that gesture felt slightly improper: too decisive. Because the atmosphere wasn’t offering “subjects.” It was offering hesitation. The light had no direction, no drama, no shadow you could trust. Everything was reduced to tonal shifts, to subtle gradients, to the kind of contrast that exists only if you’re willing to look twice. Photographing in that air is less like capturing something and more like admitting you will never fully capture it. You’re making a note. You’re writing a sentence in a language that is always half-silent.

And yet, paradoxically, this is when Venice is at its most beautiful.

Not because it is more visible, but because it is more felt. When you can’t rely on the city’s usual grandeur, you start relying on yourself: your memory, your intuition, your senses. You walk by smell. By echo. By the remembered curve of a bridge. The city becomes internal. It moves from the eyes to the body. That’s why locals don’t speak about fog as a “problem.” They speak about it the way you speak about a mood that arrives in a house: you adapt. You lower your voice. You accept that today, the world is not for long distances.

There is something protective in that. The air becomes a veil that spares you from the constant pressure of reality: the headlines, the notifications, the sense that you must always react. In that softened city, urgency loses its authority. You can’t see far so you stop living far. You stop living in tomorrow. You live in the next ten meters.

But the protection has another face. Because a veil doesn’t only shelter; it separates. It makes you feel held, and then, quietly, it makes you feel alone. In the fog, every figure becomes an apparition. A person on a fondamenta is no longer “someone”: it is a silhouette of thought. A lone walker becomes a question mark. And you realize how much of daily life is sustained by sightlines: by the comfort of being able to place yourself in a larger context. When the context disappears, you become a little more existential. You become (inevitably) more honest. You learn to take refuge without calling it retreat. You learn to let things be incomplete. You learn to accept that not everything must be resolved immediately. That some days exist precisely to suspend conclusions.

In other places, fog is a brief inconvenience. Here it feels like a philosophy with weather.

I thought about how Venice in summer is constantly asked to be legible. To be consumed. To be documented. The city is forced into sharpness: of itinerary, of desire, of image. But on mornings like this, the city belongs to itself again. It forgets it is being watched. And because it forgets, it becomes more alive. It becomes more private even in public space. The streets empty not because there is no life, but because life has moved behind doors, into cafés, into kitchens, into conversations. The city begins to breathe from the inside.

There’s a kind of nostalgia that lives in this atmosphere, but it is not the easy nostalgia of souvenirs. It is deeper; nostalgia for time itself, for the sensation that life once moved slower, that people once belonged to places more completely. In that softened city, centuries start to overlap. Not in a museum way. In a visceral way. You can imagine a man in a wool coat turning the corner in 1920. You can imagine a woman carrying bread in 1750. The fog doesn’t recreate the past; it simply makes the present less arrogant, less sure of itself. It gives history room to breathe alongside you.

And then, very quietly, you begin to understand why this city is so often associated with longing. Because longing is exactly this: loving something at the edge of disappearance.

Venice is always at the edge of disappearance: physically, metaphorically, emotionally. Water will take what it wants. Time will take what it wants. People will come and go. And on mornings like this, the city almost collaborates with that truth. It becomes less definable, less possess-able and therefore, more precious. You can’t hold it fully in your eyes, so you start holding it elsewhere: in your chest, in your pace, in the way you stop without needing a reason.

I kept walking until I reached a stretch of water where a small boat moved slowly, headlights faint as a thought. It was barely there, and yet it was everything. A whole story condensed into one moving shape. That’s the gift of this weather: it concentrates meaning. It turns the banal into symbol. It reminds you that beauty isn’t always the grand reveal.

When I finally turned back, I felt that familiar dislocation that winter in Venice sometimes gives you: the sense that the “real world” is happening somewhere else, behind the veil. And instead of panicking, instead of trying to claw my way back into clarity, I felt grateful. Because there are not many places left that can still do this: make reality feel optional for a few hours, without becoming escapist. Make you less available, less reachable, less demanded. In a season when so much of life is about enduring, this city offers another way: it offers absorption. It absorbs noise, absorbs distance, absorbs certainty.

And maybe that is why, when winter settles over Venice, you don’t just witness a change in weather. You witness a change in permission. You are allowed to be quieter. You are allowed to be unresolved.

You are allowed to walk through a city that is not trying to impress you, only to hold you (gently, ambiguously) like a hand over the flame.

By the time I reached home, the fog had not lifted. It hadn’t even begun to negotiate. It stayed there, steady and indifferent, as if it had decided to keep the city for itself a little longer.

And I thought: there are days when Venice reveals itself by hiding. There are days when the truest portrait of the city is not a skyline, not a monument, not a view at all; but a veil, a hush, a softened world in which you can finally hear your own life returning, one step at a time.

Words & Photography by Giacomo Gandola.