I Orgasmed Every Day for a Month and None of My High School French Came Back

Lex Duff

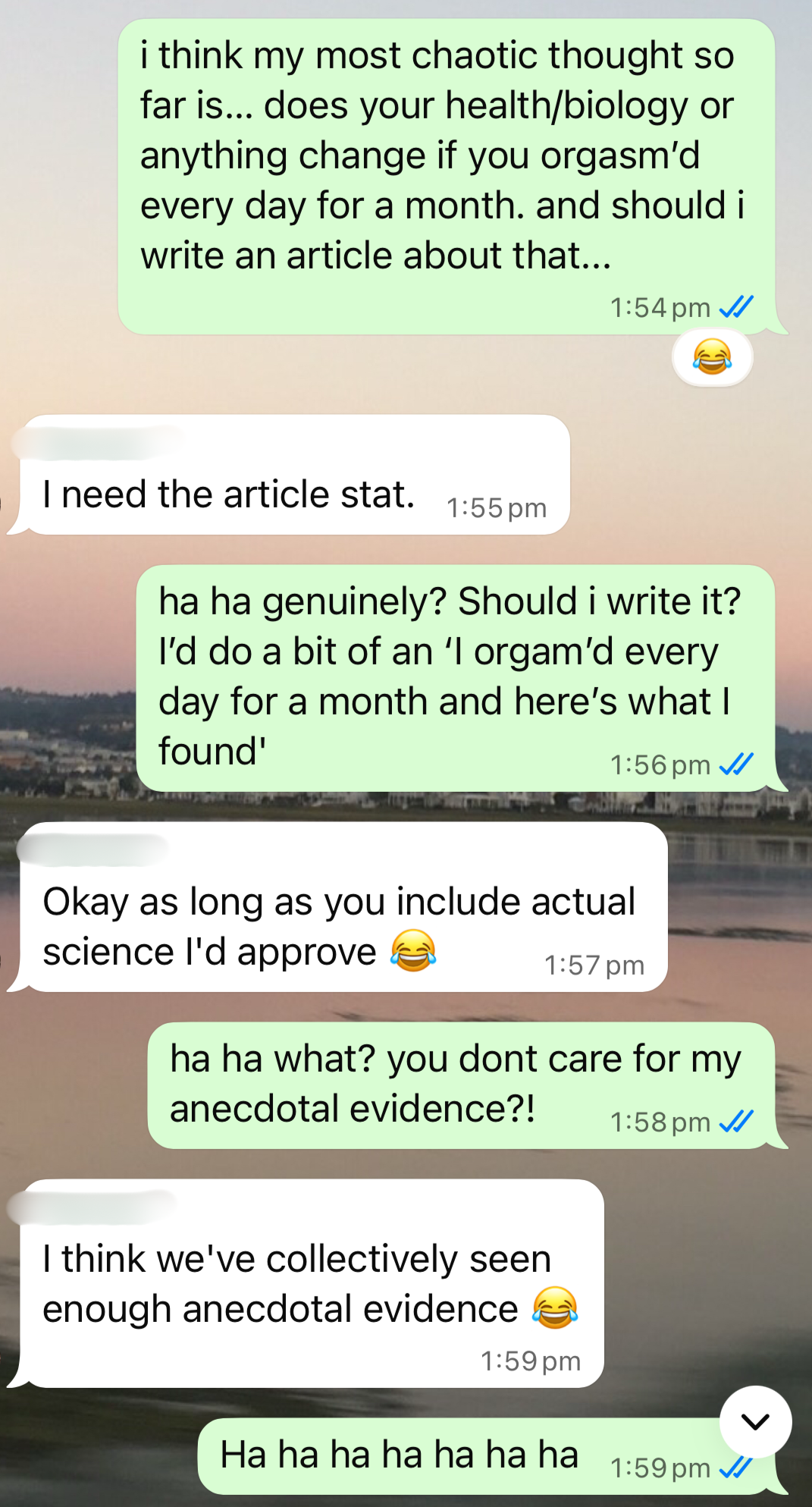

When I told my inner circle of girlfriends that I was contemplating writing an article about orgasming every day for a month, the response was immediate and, importantly, enthusiastic.

“I need this article immediately,” one friend said, without hyperbole.

Another agreed, on the condition that I include some ‘actual science’.

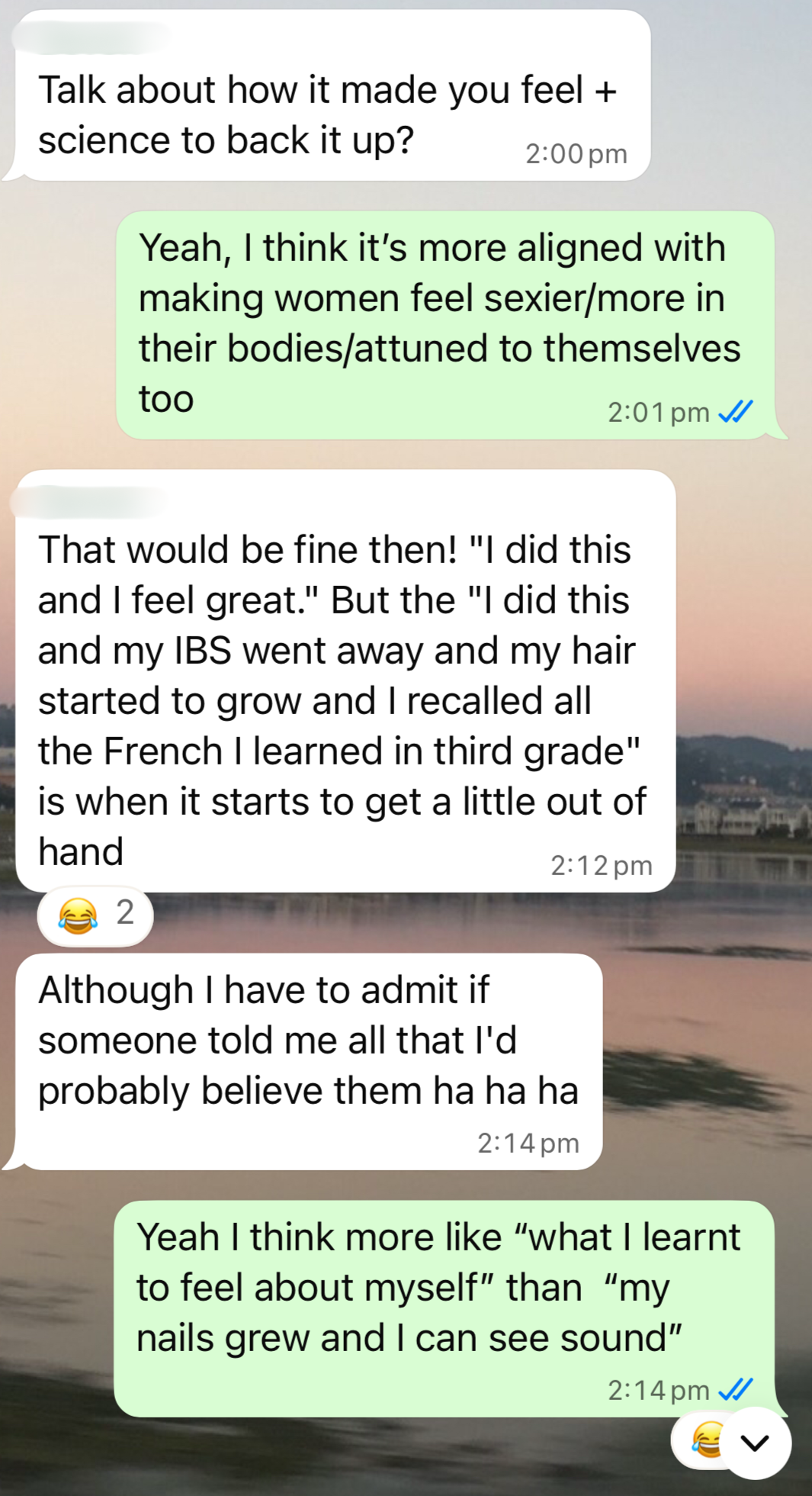

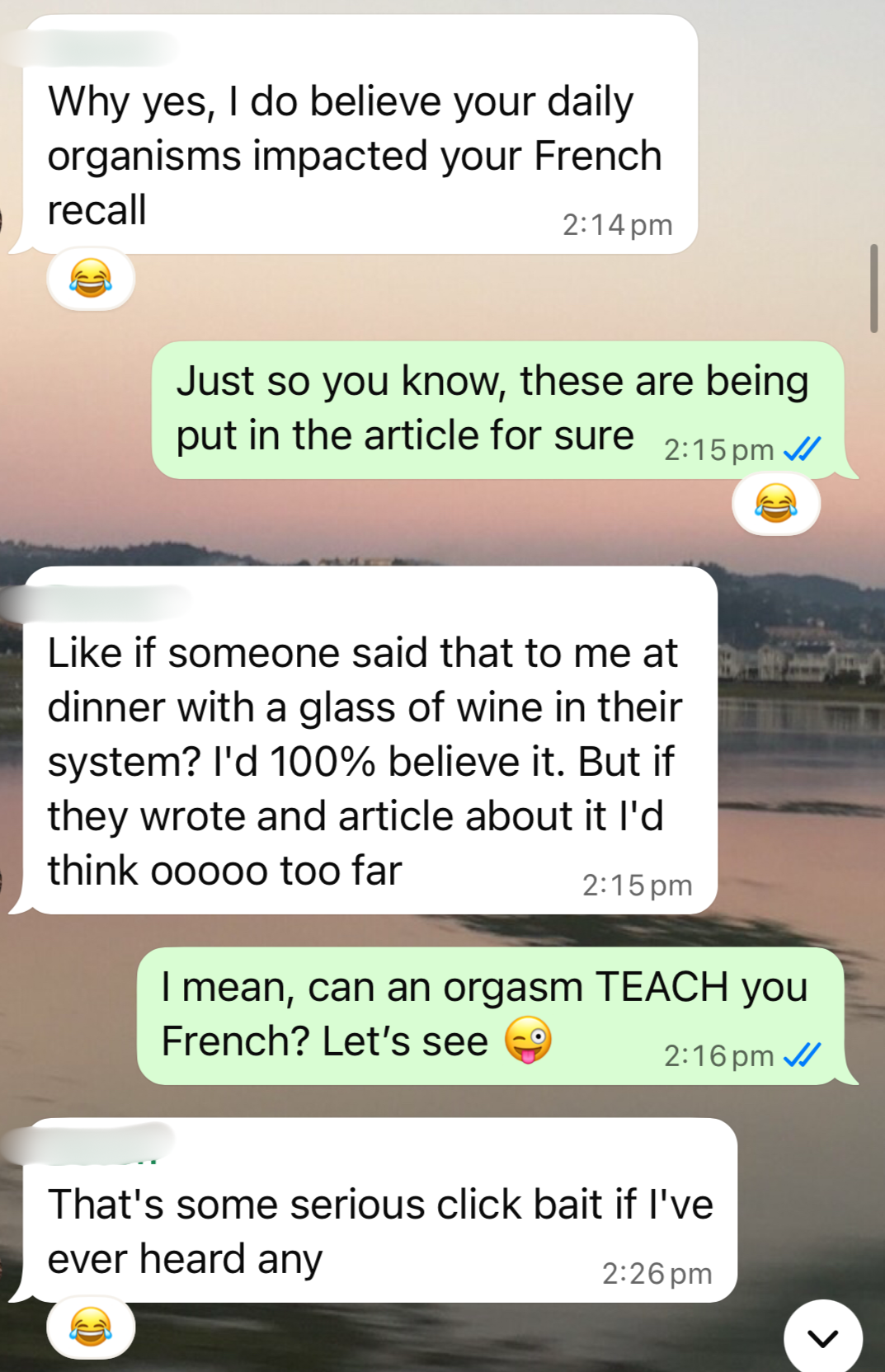

A third jokingly warned, very reasonably, against claims involving ‘cured IBS’, ‘accelerated hair growth’ or the sudden return of conversational French spoken in high school. The usual tropes we’re told that such sensual self-engagement could result in.

[For the record: no new languages were acquired.]

Still, the conversations themselves felt revealing. We laughed at the different directions a piece like this could go - the clickbait version, the wellness miracle, the deeply unhinged testimonial. And somewhere between the jokes sat the real question: what actually happens when someone makes a daily practice of her own pleasure? Not in a performative sense but just…out of curiosity.

It feels like a fitting question for an issue dedicated to Yearning. We often mistake yearning for a sense of lack - a hole that needs filling (pardon the naughty pun). But yearning is also an active state. It is a posture of leaning forward, of listening, of curiosity. To yearn for your own pleasure is to pay attention to a part of yourself that many women, and men, can be taught to outsource, delay or that they have to earn.

One of the most quietly radical things science confirms is this: your body does not care how you orgasm. It only cares that you do.

Physiologically speaking, orgasms achieved solo or with a partner produce the same cascade of effects. It is a biological reset button. It lowers cortisol (the stress hormone that keeps our shoulders permanently up around our ears) and floods the system with dopamine and oxytocin. It is a distinct softening of the nerves and as far as self-pleasure goes, it’s available to all in a biological sense.

Which I think means we can scrap the old trope that climax is a referendum on your desirability, your relationship or your sexual competence. It is not a gold star handed out at the end of a “successful” encounter. It is not proof of connection, though connection is a beautiful and important by-product. And it is certainly not something you need permission to pursue.

It is, at its most basic level, information. It is your body talking back to you.

If that sounds obvious, it’s worth looking at the numbers to see how often we ignore the conversation. According to research published in The Journal of Sexual Medicine, only around 40 percent of women report reaching orgasm during casual sex, compared to roughly 80 percent of men. With a regular partner, that number rises to 62.9 percent. Using the word “rises” feels generous. If pleasure were a workplace, we’d be staging a walkout.

The gap isn’t a mystery - it’s cultural. From a young age, male pleasure is treated as inevitable. Expected. Discussed openly, if awkwardly. Female pleasure, on the other hand, is often framed as elusive, optional, or, worse, only reactive. Something that happens if the conditions are right/perfect/virtuous.

I grew up somewhere in the silence of that gap. My sex education was almost entirely focused on prevention—preventing pregnancy, preventing disease, preventing reputation damage. Pleasure wasn't even a footnote; it was a ghost. It wasn’t until much later in my life that the idea of female masturbation even entered the conversation among friends. Not as a gag, just as a possibility. As if pleasure were something you might stumble upon accidentally, rather than something you were allowed to seek. We grew up watching Sex and the City and yet, many of us were teens at the time. The concept of owning a vibrator? Where to even start?

Which is part of why this month surprised me.

I expected the challenge to be logistical.Finding the time (alone or together), closing the door to the room and to my busy mind. But the shift wasn't about time management; it was about "noticing." Noticing my own desire, my own sensory shifts, how much ‘in my body’ it made me feel.

In the first week, there were elements of enforcement. Like flossing, but with better payoff. But by the second week, the "doing" shifted into "being." One of the most valuable things I learned was this: the brain is both the biggest obstacle to orgasm…and its greatest ally. Distraction, the grocery list, the email I didn't send? These are neurological mood killers.

The aphrodisiacal antidote? Fantasy, permission and perhaps a little focus.

About a week in, I orgasm in my sleep. It is, for lack of a better phrase, yummy but also can be frustrating literally. In that dream state, I can’t remember if I actually did ‘finish’ while sleeping so I wake up and everything takes me much longer than normal - but not in a bad way. Launching a new magazine means I have A LOT on my mind and admittedly, it’s harder to orgasm when you’re planning out your next emails.

A few days later, I realised I’ve missed a day. My mood noticed before my memory did. I voice note a friend to say I’ve woken up from a nap in a bad mood and I don’t know why I can’t shake it. In hindsight, it’s kind of obvious. Towards the end of the month, in line with my cycle, it becomes more of a self-soothing than a hunger. Seeing these shifts as the month goes on is fascinating information about my body.

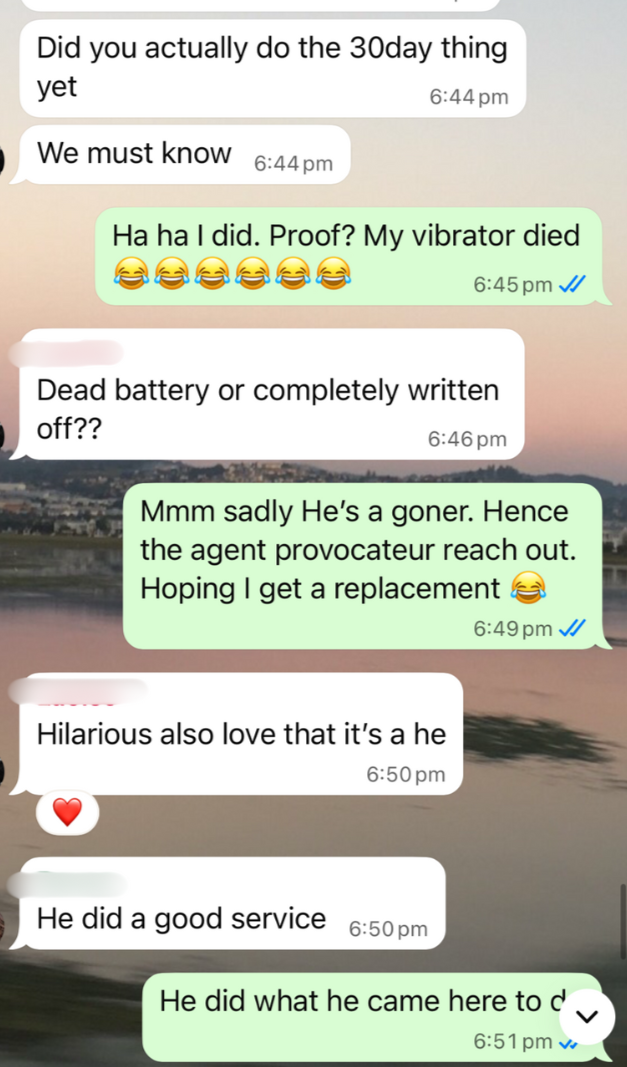

Then, there’s also the question of accessories - ‘tools’ feels like an equally appropriate word to ‘toys’, which somehow manages to infantilise women and trivialise our pleasure in one breath.

The first vibrator I ever owned wasn’t something I bought for myself. It was a gift from a partner when we were long-distance. It was one of those app-controlled ones, operated via bluetooth, from another city, another time zone. Think that dinner table scene in The Ugly Truth movie scene, but less slapstick.

At the time, I hadn’t even considered that this was something I could simply… buy. For myself. In my mid-twenties, pleasure still felt faintly ceremonial - something invited in by circumstance or another person. And yet, in retrospect, it remains one of the most beautiful gifts I’ve ever received: not because of the technology, but because it came from someone who prioritised my pleasure without centring himself in it.

Being honest, I’ve never felt the desire to bring anything additional into the bedroom with a partner. Not out of conservatism, but my own clarity. I genuinely enjoy sex with the people I choose and for me, partnered sex is about connection, presence, exchange.

The ‘sex’ I have with myself is something else entirely.

It’s not a rehearsal. It’s not substitution. It’s not compensation. It’s private, interior, and unapologetically self-directed. The two don’t compete; they don’t even speak the same language.

I was talking about this recently with a close friend - someone who has had one sexual partner in her life, her now husband. We talked about female sexual liberation and spoke about where ideas like porn sit in the moral imagination of sex: socially, religiously, domestically? We talked about the idea of using vibrators outside of sex with a partner. For her, the idea felt uncomfortably close to betrayal. She uses the word ‘lustful’, which is technically a ‘sin’ in her religious beliefs. As though desire itself, once directed inward, somehow crosses a line.

My argument - offered gently, and in earnest - is that sex with someone else and sex with myself have always felt like two entirely different experiences. Like the difference between dancing with someone and dancing alone in your kitchen. One is relational. The other is instinctive. Neither replaces the other.

In my month’s research, I come back to the words of the ever-articulate Esther Perel. “When you touch yourself, you are giving and receiving at the same time,” she says. You are both the lover and the beloved. That closed loop creates a kind of self-sufficiency that feels less like loneliness and more like wholeness.

If anything, I told my friend, knowing my own pleasure has made me a better partner. Not more distracted or demanding, but more present. When your own desire is accessible, it’s less urgent, less anxious. You’re not searching to be filled. You’re choosing to connect.

And perhaps that’s the quiet paradox: self-directed pleasure doesn’t pull us away from intimacy. It can make us more generous within it. By the middle of the month, when I hit ovulation, giving myself this month’s activity as ‘research’ means I become somewhat of a heat seeking missile (though no one complained, as such).

Once I stopped treating it like a task and started treating it like a ritual, my mind softened into it and my body followed. Eroticism, it turns out, is less about friction and frenzy than it is about memory and anticipation.

Perel noted in a recent interview that women, in the findings of studies, often tire of sexual monogamy faster than men in the setting of long-term relationships - not because they want less sex (as is so often assumed), but because they want different sex. Desire feeds on novelty, imagination, and risk. It feeds on feeling wanted and seen with fresh eyes - even if they are still the eyes of the same partner.

Understanding your own desire and orgasm - how it responds to fantasy, pacing, context- is not naval-gazing. It’s literacy. You can’t ask for variation if you don’t know what moves you.

Perel also suggests that women are often narcissistic in desire in a specific way: we are turned on by the idea that we turn you on. Our desire is reflective. Relational. We are used to being the object of desire, rather than the subject. The madonna, whore and the muse.

Prioritising solo pleasure disrupts that loop. When you are alone, there is no one to perform for. No one to validate the curve of your hip or the sound of your breath. You are forced to move from "Am I desirable?" to "Do I desire this?"

What shifted most for me wasn’t frequency. It was posture. As I’ve become more comfortable in this space, I’ve realised that these days, I rarely feel sexier than in that environment - solo or not.

There is something quietly transformative about seeing yourself as a sensual being, a sexual being, a being who yearns and wants with self-permission. It changes how you move through the world. It changes how you inhabit your skin. At least it does for me.

This wasn’t about becoming louder or brasher or more sexualised. It wasn’t even just about the shock value of this article’s headline. If anything, it felt grounding. A private calibration.

And perhaps that’s why it still feels faintly defiant. Orgasms are ancient. They predate romance, religion, and most of our shame. And yet, for women, choosing pleasure without apology still carries the thrill of rebellion.

On the last day of the month, I didn't have a grand epiphany. I did host a small moment of silence for my vibrator that, timed exquisitely, gave up the ghost. But the sky didn't open. I still had to do the laundry.

I still couldn't conjugate French verbs in the past tense, much, I’m sure, to my high school French teacher’s dismay. This month did not cure anything. It did not make me better or smarter.

My orgasms didn’t finish my to-do list or cook dinner or write this article. But fuck me (again, with the puns), were they delicious and fun.

They made me more attuned. More imaginative. More at home in my own wanting.

Which, for a life of yearning, feels like the point.